MYTH on

the MAP

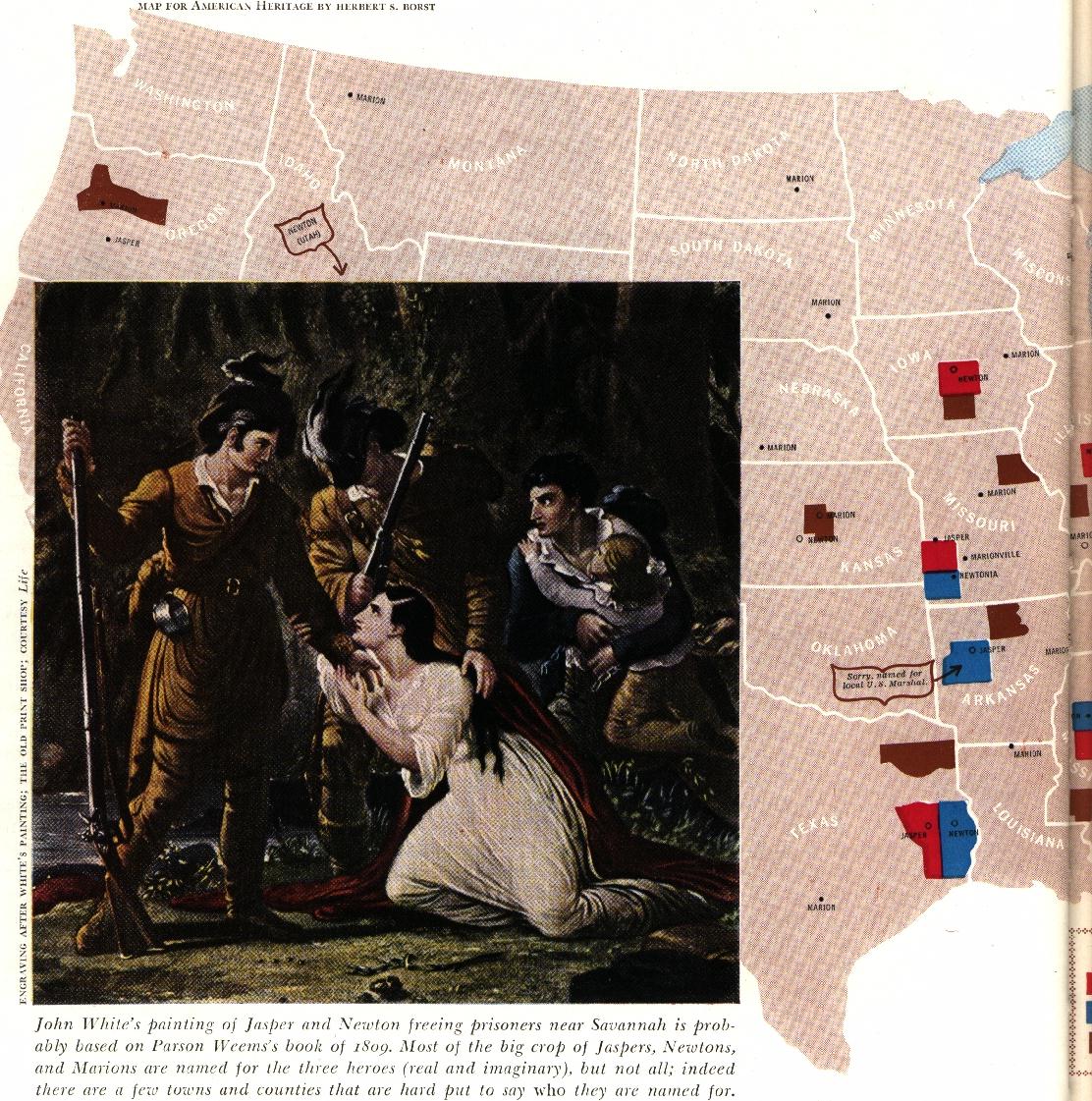

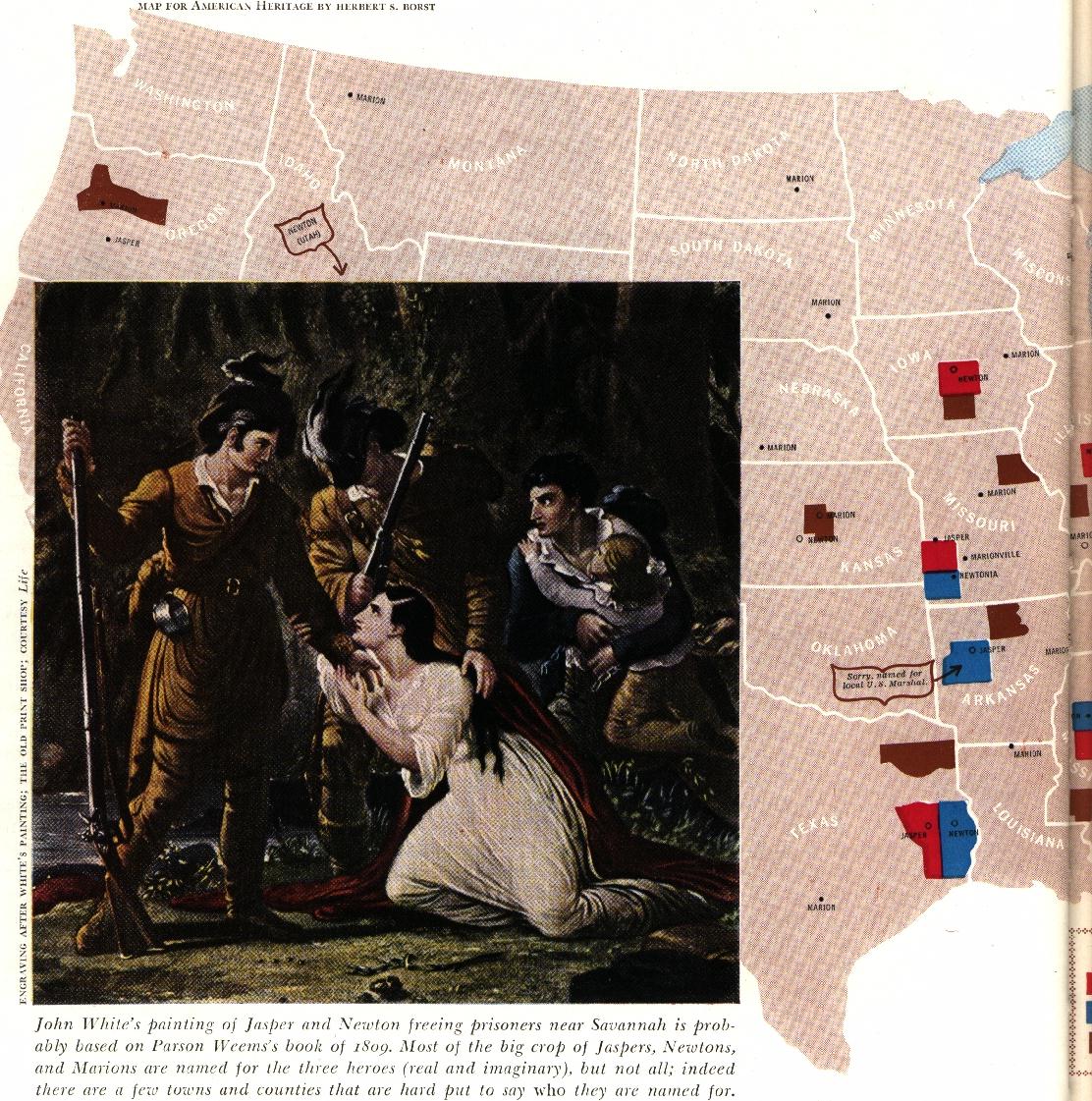

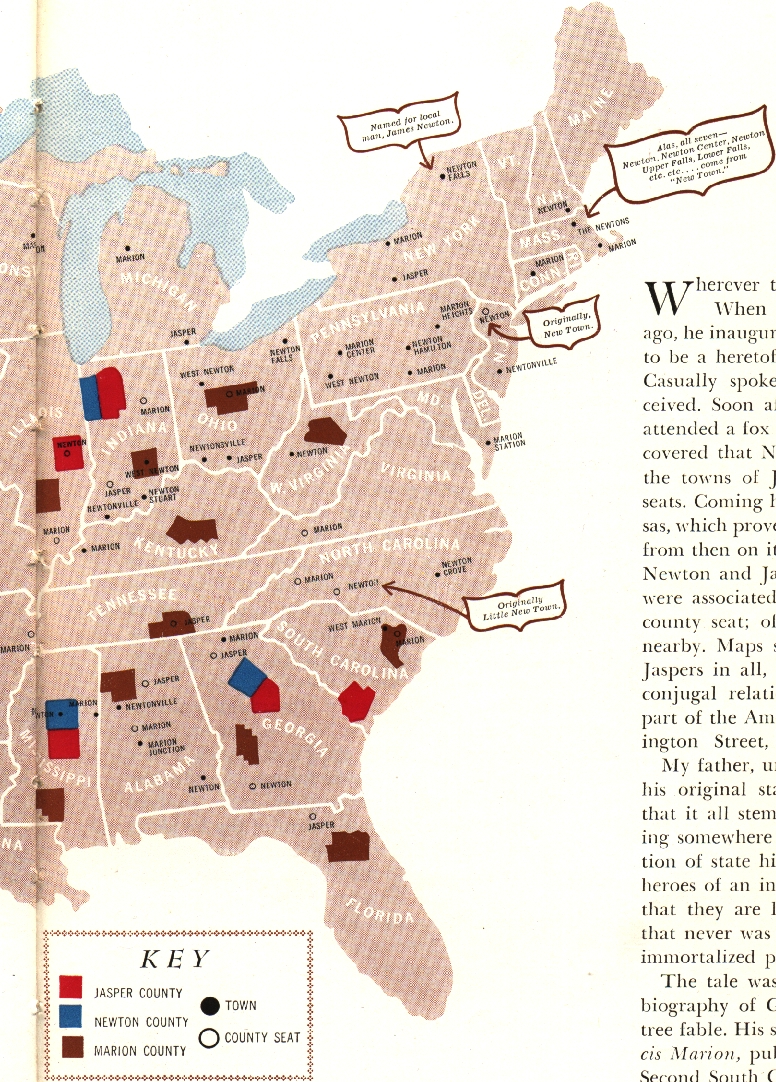

Scores of towns and counties all over the nation honor

some heroics largely invented by Parson Weems

By LOU ANN EVERETT

Wherever there's a Newton, there's a Jasper."

When my father said that to me three years ago,

he inaugurated a search that reveals what I believe to be a heretofore

unrelated bit of American history. Casually spoken, his remark had

been casually received. Soon afterward, however, my husband and I

attended a fox hunt in Jasper County, Texas, and discovered that Newton

County was next to it and that the towns of Jasper and Newton were their

county seats. Coming home, we drove through Jasper, Arkansas, which

proved to be the seat of Newton County, and from then on it seemed that

no matter where we went Newton and Jasper were on the way. Sometimes

they were associated as counties, sometimes as county and county seat;

often a town or county of Marion was nearby. Maps showed more than

sixty Newtons and Jaspers in all, half of them juxtaposed in an almost

conjugal relationship. They were about as much a part of the American

scene as Lincoln avenue, Washington Street, and Courthouse Square.

But why?

My father, unfortunately, had offered no reason

for his original statement beyond the vague suggestion that it all stemmed,

somehow, from a painting hanging somewhere in South Carolina. My

own investigation of state histories reveals that they commemorate heroes

of an incident that may never have happened, that they are linked together

because of a dialogue that never was spoken, and that one of the men thus

immortalized probably was a thief and a villain.

The tale was told by Mason Locke Weems, whose biography

of George Washington created the cherry tree fable. His second book,

The

Life of General Francis Marion, published in 1809, dealt largely with

the Second South Carolina Infantry Regiment of Revolutionary War fame,

and there it was that "Parson" Weems related the exploits of two of Marion's

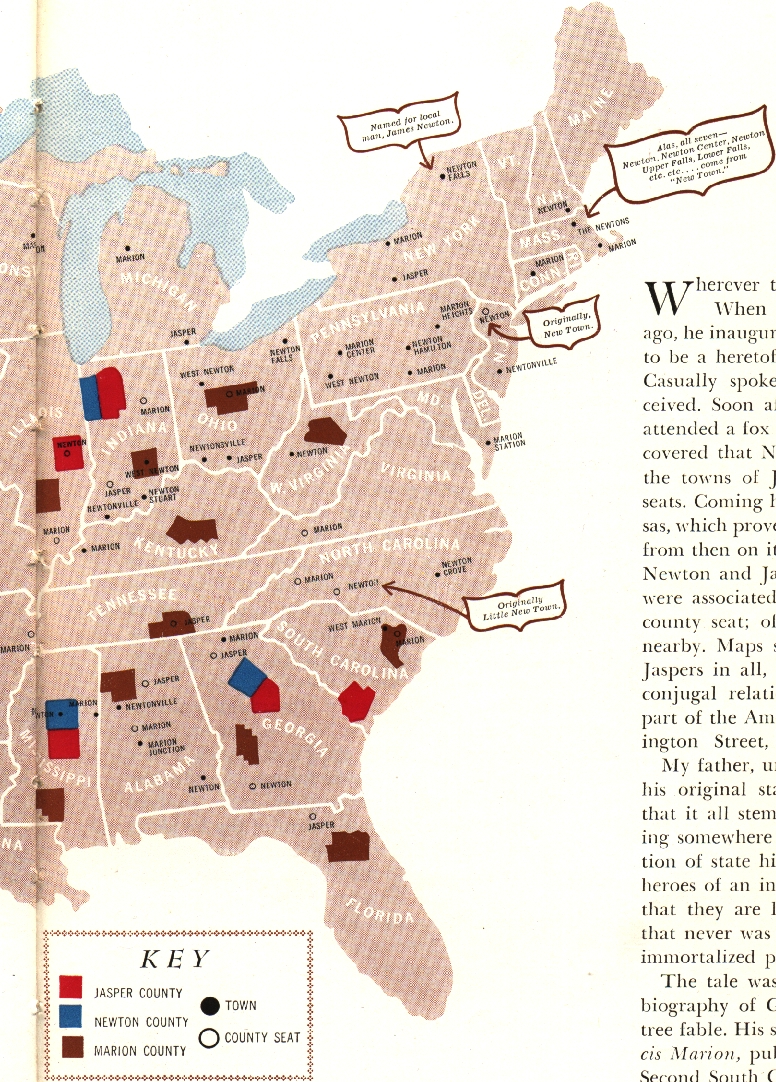

sergeants, Newton and Jasper. One day in the spring of 1779, the

Parson related, the pair emerged from their hiding place beside a spring

near Savannah and dramatically rescued a number of American prisoners,

among them a woman and child, from a party of ten British captors.

In the process, the two Americans disposed of one enemy sergeant, one corporal,

and two privates, capturing the remaining six, while they themselves were

not even scratched. According to Weems, Jasper and Newton were at

no loss for rich, fruity dialogue as they embarked upon their heroic deed.

Let the good Parson tell it:

The brave are always tender-hearted. It was so

with Jasper and Newton, two of the most undaunted spirits that ever lived

. . .

"Newton," said [Jasper], "my days

have been but few; but I believe their course is nearly done."

"Why so, Jasper?"

"Why, I feel," said he, "that I must

rescue these poor prisoners; or die with them; otherwise that woman and

her child will haunt me to my grave."

"Well, that's exactly what I feel

too," replied Newton--"and here is my hand and heart to stand by you, my

brave friend, to the last drop. Thank God, a man can die but once;

and there is not so much in this life that a man need be afraid to leave

it, especially when he is in the way of his duty."

The two friends then embraced with

great cordiality, while each read in the other's countenance that immortal

fire which beams from the eyes of the brave, when resolved to die or conquer

in some glorious cause.

Conquer they did. Nor was the liberated lady

ungrateful. Weem's narrative continues:

. . . She exclaimed, "Where? Where are those blessed

angels that God sent to save my husband?"

Directed by our looks to Jasper and

Newton, where they stood like two youthful Samsons, in the full flowing

of their locks, she ran and fell on her knees before them, and seizing

their hands, kissed and pressed them to her bosom, crying out vehemently--"dear

angels! dear angels! God bless you! God Almightly bless

you forever!"

The story was accepted as gospel by the literalistic

people of the day, and ever since then the gallant Newton and the undaunted

Jasper have been standing staunchly side by side--even thought the one

man who undoubtedly knew the true facts said it simply wasn't so.

That was Brigadier General Peter Horry, whose own name was on the book's

title page along with that of Weems. Horry had written and given

to Weems a sketch history of Marion's brigade, and the redoubtable Parson

had promised to get it published. Horry had admonished him "not to

alter the sense or meaning of my work, least when it came out I might not

know it; and, perverted, it might convey a very different meaning from

the truth."

When the book appeared, Horry was horrified.

He wrote to Weems, ". . . You have carved and mutilated it . . . Most certainly

'tis not MY history, but YOUR romance." Horry's indignant disavowels

went unnoticed by a public that would not be denied its heroes. In

the years after the book was published--for the most part between 1820

and 1850--new towns and counties springing up all over America adopted

the names of one or the other of Weems's bold sergeants.

In William Jasper, at least, the public was not

entirely deluded. He was a bona fide hero, whom General William Moultrie

called a "brave, active, stout, strong, enterprising man, and a very great

partizan," and "a perfect Proteus in his ability to alter his appearance."

He held a roving commission as a scout and part-time spy, but mostly he

is remembered for rescuing his regimental banner during the bombardment

of Fort Sullivan (later called Moultrie) in 1776, after which new colors

were presented to the regiment by a Mrs. Susanna Elliot, Jasper died defending

them during the siege of Savannah.

Weems seems to have used his imagination freely

in creating that "blessed angel" of the fiery eye and brave demeanor, Sergeant

Newton. He said that Newton was Jasper's "particular friend . . .

son of an old Baptist preacher and a young fellow for strength and courage,

just about a good match for Jasper himself." But Horry, uselessly

of course, wrote: "Jasper was an Honest Man; but Newton was a Thief &

a Villain." Since neither Weems nor Horry gave Newton a first name,

it is hard to prove just who he was. Four Newtons served with the

regiment, but two were fifers and another a private. The only Sergeant

Newton--his name was John--was discharged on April 17, 1778, a year before

the alleged exploit at Savannah.

The inscription on the Jasper Monument in Savannah

doesn't mention Sergeant Newton, but his name does appear on a marker that

now stands a few miles west of Savannah at Jasper Spring, the site of the

alleged incident. All later writings seem to take Weems's book as

the ultimate source of the incident, but perhaps the basis for the entire

story was this excerpt from an article in the Virginia Gazette of

May 15, 1779: "The brave Sergeant with another seargeant, crossed Savannah

River, took, and brought to Major General Lincoln's headquarters, two Captains,

named Scott and Young, of the British troops in Georgia."

It is unlikely that we will ever know the real truth

of the matter, and it doesn't seem quite fair to the memory of General

Horry. Weems was applauded for his writing, Jasper and Newton were

honored throughout the land, but Horry had just one little county in South

Carolina named after him. And after all, it was his notes, mightily

improved upon by the Parson, that started the whole thing.

Mrs. Lou Ann Everett, a former reporter for the Tulsa

World,

now lives in Sand Springs, Oklahoma, where she and her husband publish

a weekly newspaper, the Times, and a national fox-hunting monthly

called The Hunter's Horn.

[This article appeared in the December, 1958, American Heritage.

It has been reprinted on the Web, without permission, in reply to a question

raised on the Roadmaps-L mailing list. It's appearance here is temporary.

Unreadable due to the page split in the above image are Marion, Wisconsin,

and Newton, Mississippi. Parson Weems was behind a whole slew of

myths about early American history which will apparently haunt us

forever. --16 July, 2000]